Studies have found that kidney stones are occurring more frequently in children.

Researchers looking at emergency room admissions in South Carolina found an increased occurrence of stones between 1996 and 2007 from 7.7 and 8.0 per 100,000 female and males to 21.9 and 15.3 per 100,000 females and males. Unlike in the adult population, stones in children appeared more commonly in females than in males.

“Alex” was an otherwise happy and healthy 6-year-old girl until she developed recurrent urinary tract infections. She was treated with antibiotics after seeing her pediatrician but continued to have infections that did not respond to treatment. Eventually, she underwent a CT scan that found a very large 1.8 cm right kidney stone. After going over her options with her treating urologist, her mother decided on treatment with a percutaneous nephrolithotripsy procedure given the large size of the stone. She underwent surgery successfully but developed some persistent drainage from her surgery site, which was thought to be secondary to a blood clot temporarily blocking her ureter after surgery. This eventually passed on its own and after a 3-day hospital stay, she was discharged home. Her stone analysis demonstrated that it was composed of a mixture of types, including 70% calcium oxalate dihydrate, 20% calcium oxalate monohydrate, and 10% calcium phosphate. With her stone gone, she has not had any further problems with urinary tract infections and is back to normal.

Dietary causes of stones in children

Many experts have pointed to societal changes in dietary habits as the culprit for the increase in kidney stones seen among children. The well-publicized rise in fast food, junk food, and soda consumption by children not only has contributed to alarming rates of pediatric obesity in the United States but also has led to several dietary changes that make it more likely that kidney stones will form. These dietary risk factors, similar to those seen in adults, are outlined below.

High salt intake has been shown to increase the concentration of calcium in urine, making it more likely for calcium-based stones to form. Eating more processed meals and snacks as well as eating more fast food leads to an increased salt intake in children due to the high sodium content in these foods. Sports drinks are an additional surprising source of sodium in the diet.

High protein intake from meats increases uric acid, calcium, and oxalate levels, and reduces citrate levels. All these metabolic changes can increase the risk of kidney stones. The tendency of American children to eat too much meat and not enough fruits, vegetables, and grains has recently been in the spotlight as part of the USDA’s “ChooseMyPlate.gov” initiative.

Low calcium intake can increase the risk of stones because it allows more oxalate to be absorbed in the gut. Therefore, a normal calcium intake is recommended for those at risk of stones. The popularity of drinking sugared beverages including sodas, sports drinks, and fruit juice flavored drinks in the place of milk can be blamed for the inadequate calcium intake seen in some children.

Dehydration leads to low urine output, increasing the concentration of stone promoters in the urine such as calcium, oxalate, and uric acid. Increasing fluid intake to keep the urine dilute and clear is one of the most effective means of reducing the risk of all types of stones. Some children tend to not drink enough fluids, in part because they want to avoid the need to use the restroom, especially during school or playtime hours.

Obesity has been linked to an increased risk of stone formation in adults. It may do so by changing the adult body’s metabolism to be more acidic, which results in an increase in calcium excretion and a decrease in citrate excretion. However, obesity may not be the reason why more children are also developing stones. A recent study reviewing a large number of children with kidney stones found that obesity did not appear to increase their risk of stones, unlike the situation seen in adults.

Other cause of kidney stones in children

Topiramate, an antiepileptic drug sometimes given to children, is an uncommon cause of pediatric kidney stones. Those children on the medication appear to have a two to four fold increased risk of kidney stone development compared to children not on the medication. Topiramate is thought to cause metabolic changes that increase the risk of forming calcium phosphate stones through lowering urine citrate, raising urine calcium, and raising urine pH.

Melamine, an illegal industrial additive used to artificially boost the measured protein content of food, was recently at the center of a scandal involving tainted baby formula in China in 2008. Children given the formula were found to develop kidney stones and in some cases kidney failure. The melamine appears to have combined with cyanuric acid, also present in melamine powder, to form crystals in the urine that gave rise to kidney stones. In some cases where many small crystals formed, kidney failure developed while in other cases, larger stones developed. The number of children affected was estimated to range between 54,000 to 300,000. In a study of 421 children given tainted formula, researchers found that 50 had evidence of kidney stones. Chinese authorities convicted 21 individuals in association with the illegal practice of melamine adulteration, with three receiving death sentences and three receiving life sentences.

Cystinuria, an inherited disorder that results in the abnormal handling of amino acids in the kidney and small bowel, can cause kidney stones due to abnormally high levels of cystine in the urine. It is the cause of 1-2% of all kidney stones and 6-8% of stones in children. Hydration and medications are used to help reduce the number of stones formed in patients with this disorder but surgical intervention is often required because of the frequency of stone development.

Primary hyperoxaluria is a rare inherited disorder that can also cause stones. Because of defective enzymes in the liver, high levels of oxalate build up in the body and are excreted into the urine. These high levels of oxalate lead to the development of calcium oxalate stones. Patients with the disorder may be diagnosed with stones from birth to their twenties. Many end up developing kidney failure (80% by age 30). The Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation estimates that the disease occurs in between 1 in 100,000 and 1 in 1,000,000 births. Primary hyperoxaluria is distinct from the more commonly found “enteric hyperoxaluria” which can also lead to high levels of oxalate in urine among stone formers. In enteric hyperoxaluria, abnormal over-absorption of oxalate occurs in the bowel due to intestinal disorders, particularly among individuals who have undergone gastric bypass surgery. Eating excessive oxalate containing foods (dietary hyperoxaluria) and over-absorption of oxalate by normal intestine (idiopathic hyperoxaluria) can also lead to high levels of oxalate in the urine. The oxalate levels seen in these three disorders is usually much lower than the levels seen in primary hyperoxaluria.

Malnutrition in children from developing countries can lead to endemic bladder stones. These are formed when a diet consists of mainly grains without adequate animal protein or cow’s milk. Additional factors leading to stones in these children include dehydration, infection, and a dietary deficiency in phosphate. Children with these stones are typically younger than 10 with the most common age of diagnosis being 3 years. Stones may pass on their own if they are small but can also form as large bladder stones that need to be surgically removed.

Diagnosis of kidney stones in children

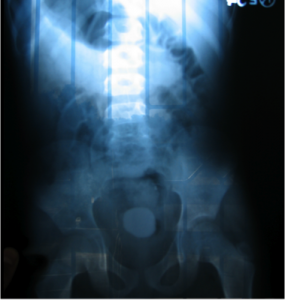

A child with a kidney stone may present with symptoms including non-specific abdominal pain, vomiting, or pain in the back radiating towards the groin. Blood in the urine, burning on urination, and increased frequency of urination can also be associated with a stone. These symptoms can also be common in other illnesses, including urinary tract infection, constipation, appendicitis, or gastroenteritis. Therefore, evaluation by a physician is important in order to make the correct diagnosis. Imaging studies will be used to confirm a diagnosis of a stone and may include ultrasounds, plain x-rays, or computed tomography (CT) scans.

Treatment options for kidney stones in children

Treatment options in children mirror that for adults although an emphasis is placed on minimizing surgery if possible given the smaller anatomy. Because of this, observation and allowing a stone to pass by itself is preferred, if possible. However, stones larger that 4mm in size are less likely to successfully pass and are candidates for surgical intervention. Here, the options are similar to those in adults and include shockwave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, and percutaneous nephrolithotripsy. Shockwave lithotripsy is often considered the best first choice due to the fact that instruments do not need to be inserted into a patient and the generally lower amount of pain experienced during recovery. The option for ureteroscopy can sometimes be limited by the smaller size of pediatric patients, which may not accommodate insertion of the necessary instruments. Percutaneous surgery in children is reserved for larger stones and is also sometimes used when a child is too small for ureteroscopy.

References:

- Sas and coauthors: “Incidence of kidney stones in children evaluated in the ER is increasing”. Journal of Pediatrics, 2010

- Schaeffer and coauthors: “Medical comorbidities associated with pediatric kidney stone disease”. Urology, 2011.

- Welch and coauthors: “Biochemical and stone-risk profiles with topiramate treatment”. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 2006.

- Guan and coauthors: “Melamine-Contaminated Powdered Formula and Urolithiasis in Young Children”. New England Journal of Medicine, 2009.

My 6 old son has kidney stones we have ended Primary Children’s Hospital and I still don’t have very many answers and I’m worried